The question "Who am I?" is not culture or age specific. However, few would dispute that the idea of the self as a specific idea or consciousness is most characteristic of contemporary, primarily Western thinking.

"The deepening integration of the social sciences into other disciplines is also leading the discourse towards an emphasis on Eriksonian identities. Identities are all around us: a political party, a congregation, a civil movement or a museum's mission statement. To move away from this, some kind of intercultural appropriation is almost indispensable.

Of the three basic states of Buddhism one, the egolessness is not the denial of the self, but the non-self-connectedness of anything perceived by our senses. The image of the self is therefore not equal to what our brain has created, as thoughts, perceptions and consciousness are constantly changing. The Buddhist therefore aims to get rid of the self-image identified by perception and thought in order to reach the higher self.

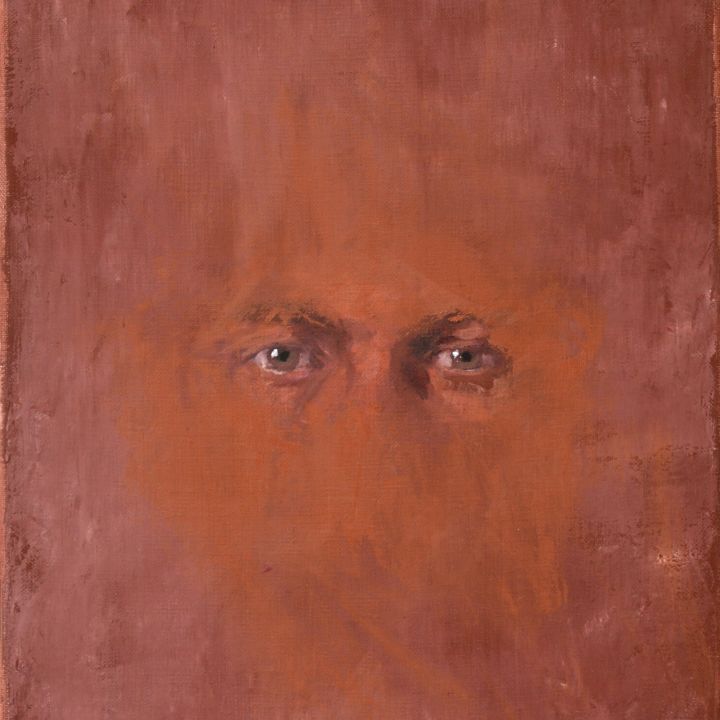

Martin Henrik's attempts at self-determination are also an attempt to get rid of something. The artist achieves this liberation by looking in the mirror in semi-darkness by concentrating only on the eyes. At an advanced stage in the process the eyes are sharpened, but the rest of the face becomes blurred. The phenomenon of peripheral vision was described in many optics treatises in the 19th century, not coincidentally at the same time as the invention of photography and also explained the work of some portraitists, who painted the face accurately - in today's terms, 'sharply' - while the rest of the figure was blurred.

After and in parallel with his preoccupation with space Martin turns his attention to inner space when he looks into a reflective surface. But this is not the first time that the artist has addressed this question in his exhibition Vidya: his box of blackened glass, which he made more than ten years ago invites the visitor to meditate and is activated by pressing a button and which also explores a similar optical illusion. He calls his experiments in his current series, ironic procedures for undermining self-belief, "exercises", meaning that he sees them not as a one-off solution but as a task that can be repeated several times, perhaps in preparation for a future situation. In any case, the emphasis is on the process. On canvases painted in oil or egg tempera or reliefs carved in basalt, only the least changeable part of the face - the window to the inner self, to put it more colloquially - the eye, can be clearly seen.

However, the eye is not only an expression of the inner spiritual world, but also one of the most important organs of orientation in the outside world. And this external world has an effect on our self-image, from which we must free ourselves in order to reach a state of egolessness.

Through the expressive power of the eyes it is sometimes possible to identify the age and state of mind of the figure in the painting. The artist is, of course, present in all of them: the cliché often heard about portraitists, that in their portraits of others they always paint a little of themselves, is self-evident in this case. In some of them the seated posture of the artist's well-known Buddha statues is faintly visible, so that it is not a portrait but a full-length representation. Sometimes the other facial features, which have been thoughtfully placed alongside the solitary eye are not positioned in the usual place within the picture, thus making the viewer feel unsure.

It almost goes without saying that the sculptor, who graduated in painting and has now been painting a lot again for a year, also used the grisaille style to create his Vidya series. Painting in grey has been used many times in the history of art by artists to achieve a sculptural effect more cheaply and quickly, and to challenge the basis of the rivalry between the two disciplines, which is that painting is less able to reproduce three-dimensionality than sculpture. In the case of canvas, the viewer is more forgiving, can more easily imagine the other features of the face, accepting that the painter has not yet painted or perhaps repainted the missing parts. The faceless, mouthless versions carved from basalt lead us to the exhibition's companion theme, the astrometric objects. Their shape is reminiscent of Georges Méliès' iconic facial moon of 1902 and their placement is reminiscent of the head-shaped arched architraves of medieval buildings.

However, the connection between the two seemingly easily separable groups of works is established by the objects themselves, when we are confronted with the Konkáv Meditation Object carved in granite and the sitting, meditating figure, both contemplating each other and at the same time meditating on themselves. They must have already reached a state of vidya, of alertness, of awareness, because they know the most about themselves. So let them have the 'word'."

Opening text by Zsuzsanna Szegedy-Maszák