This poem was written by Christian Morgenstern. The poet has written volumes of nonsense poems like this and more. Some of them are nothing more than high-minded absurdity, a mockery of life. At the same time a deep philosophical bent is evident in these tiny grotesque games, for the muse, while tumbling 1*, looks at existence from a strange angle that she never has the opportunity to do in a sublime pose. This poem is also about the seductive choice of perspective. And that's why it fits here. Not to mention his intimate relationship with cork stoppers...just look at his bush full of cork stoppers.

Speaking of cork stoppers! At the 2007 Venice Biennale I saw a work by an African artist (El Anat-sui, a Ghanaian-born Nigerian) that has been memorable to me ever since: he created unimaginably beautiful tapestries out of soft drink bottle tops. How does this fit in? What do the beautiful draperies have to do with the charmingly bumfordian, fairy grotesque figures of Györgydeák? Well, here's the thing: it's a way to turn rubbish into gold. Because Györgydeák can make gold from scrap wood, string, tow, nails, sand, plaster, clay, bits of old utensils, decaying linens, furniture from his ancestors and friends, broken toys from his children... and I could go on and on with the things he used to assemble most of his puppets and tableaux - in short, everything that we used and threw away in the service of his demiurgic imagination.

From here, there are several paths leading to his world.

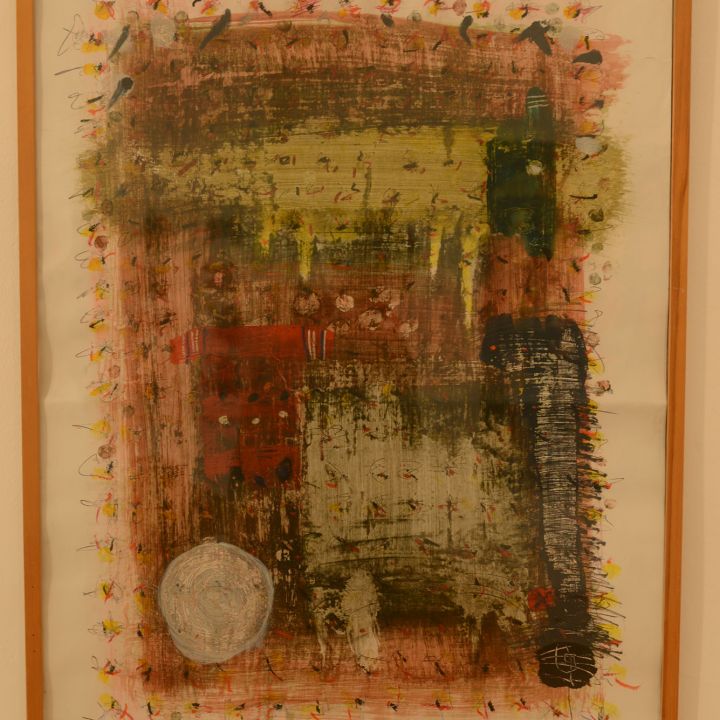

The African artist just quoted is also a link for another reason: we all know that one of Györgydeák's most important experiences was his art expedition to Western Sahara. Thus, he consciously cultivated the collage technique and style of form that Picasso's once began more than a hundred years ago. Ready-made objects assembled from used objects have really been around that long. But Györgydeák purified these found objects.2** That is, he considered life itself to be a kind of found object, which one receives in addition on death and thus can return it at any time - that is why it is preserved.3*** Well, and he, who so quickly returned this found object, his life; he knew well that the found objects would be incorporated as domestic ghosts or at least as house-elves into the artist's life, home and studio: into his works. As we can see in his work "The Occupation of the Homeland".

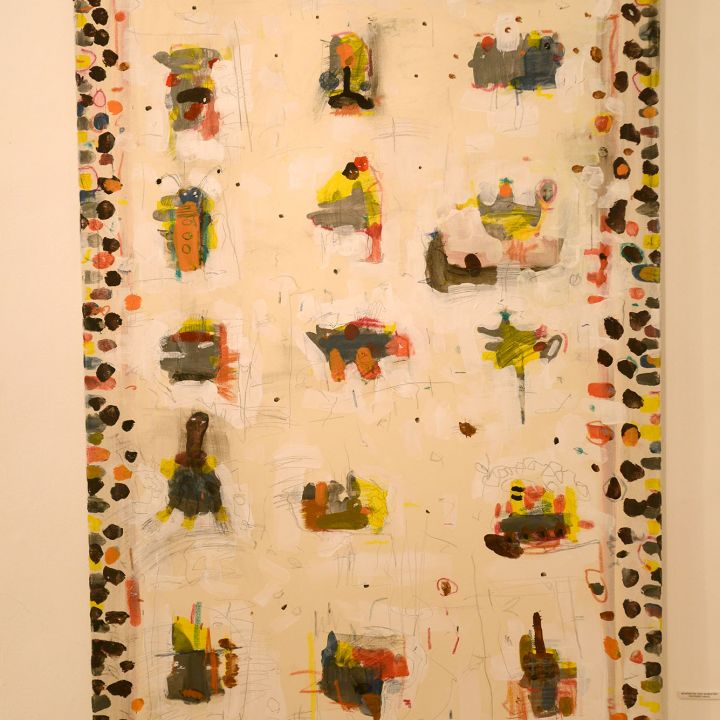

The other path also reaches a crossroads here: this image is emphatically iconic. And from here you can see that all the others are. Györgydeák's panels are windows on eternity. They are icons. They are manifestations of a kind of religiosity. 'Bübüs' are as much a part of his private religion/private mythology as are the strange, animal- or human-like half-beings in his paintings, prints and panels. They have a name and a highly imaginative one rivaling Morgenstern's and Ervin of Lázár, who invented Dömdödöm. And a story! As if Mrs. Pegasus, the opera singer with the sore throat, Black Feather, Red Beak, Lauz Szimacs... and the others knew each other and each other's stories!

Initially, it was perhaps instinctive that what Györgydeák drew and painted resembled László Réber, who resembled children's drawings. Then the Saharan experience made him more conscious of this: the African rock drawings created for him the 'developed era' of Kenese (as the title of a panel painting says). Kenese is, of course, the centre of the world. But anyone who sees the world in this way is necessarily on a reservation. For Györgydeák, being on a reservation seems to come naturally. And so it is that he became an Indian (as the title of his album, in addition to many of his works, also says) - so much so that the Bakony Indian tribes of Tamás Cseh could gladly make him an honorary member, even chief, of their tribe - at least in retrospect. Another good thing about Kenesse is that there is big water - something that was necessarily missing from the Sahara experience - so the proximity to nature naturally led to the boat creations. Because "navigare necesse est"; never backwards, always forwards - the captain asked for a good wind.

Seen from this reserve and also from the hunched posture the so-called reality looks different. This is the reason for the multitude of 'post-art nouveau' views of Veszprém, full of ironically swooping buildings, which can also be seen here. They are a bit like the "hexagon" of Kós Károly's engravings of buildings: there is not a single straight line in these pictures - certainly not a right angle. And in this context I must return to the pseudonymity of the Bübü's and the panels. The grotesque-playful charm, the apparent clumsiness actually conceals a strong drawing skill, a professional confidence, that is to say, it is seductive. This is evident precisely in the cityscapes. As is the fact that Györgydeák could fly - even though many of the Bübüs resemble some kind of shapeless, flightless bird. The artist was obviously secretly in love with birds: they are symbols of soul and freedom. His cityscapes, his panels, his Bübüs all speak of freedom. A sense of humour, without which man is fearsome. For everything is lost on a man without humour and playfulness. People who see the world in a "abstract" way and think in right angles. Power, business, in short, all those demented spheres that take themselves too seriously, will grimace here tonight. Deo Gratias!

For this reason alone - but not only - Györgydeák's works can be said to be sacral.

I started with a poem by Christian Morgenstern. One of his critics wrote that he either had to die because of his particular vision of the world - or create a world of his own. Györgydeák György created a world of his own. But he also died into the existing world. Too early. He would now be - only - fifty-five years old. And it is now five years since he has been able to "look at himself from there", as he put it in the title of one of his pictures. While he was alive, I hardly knew him - I saw him only a few times. Some things can never be put right again. This is one of them. But perhaps he really is looking at you now "from there", as we are looking at him here, for example, in his figure of a rabbit.

And Someone Else is looking at him. And this brings us back to the problem of perspective that we touched on at the beginning.

Christian Morgenstern: Vice Versa

Ein Hase sitzt auf einer Wiese,/ des Glaubens, niemand sähe diese.

Doch, im Besitze eines Zeisses,/betrachtet voll gehaltnen Fleißes

vom vis-a-vis gelegnen Berg/ ein Mensch den kleinen Löffelzwerg.

Ihn aber blickt hinwiederum/ ein Gott von fern an, mild und stumm.

Vice Versa

A hare sits in a meadow,/ believing that no one sees it.

Yet, in possession of a Zeiss,/ a man observes with sustained diligence

from the mountain opposite/ a man looks at the little spoon dwarf.

But in turn/ a god looks at him from afar, mild and dumb.

* The Tumbling Muse anthology is a collection of nonsense-grotesque-humorous poems

** Tandori Dezső: Cleaning up a Found Object

*** Quote from the poem Awekening/Eszmélet by Attila József. The title of the Tandori volume also quotes it, of course.

Zsuzsa Veress' opening speech