Between 1968-72 she studied at the Secondary School of Fine and Applied Arts and from 1976-81 she was a student of Pál Gerzson at the University of Fine Arts.

After graduating from the University she was a member of the Studio of Young Artists until 1988 and from 1980 she has been a member of the Fine Arts Fund.

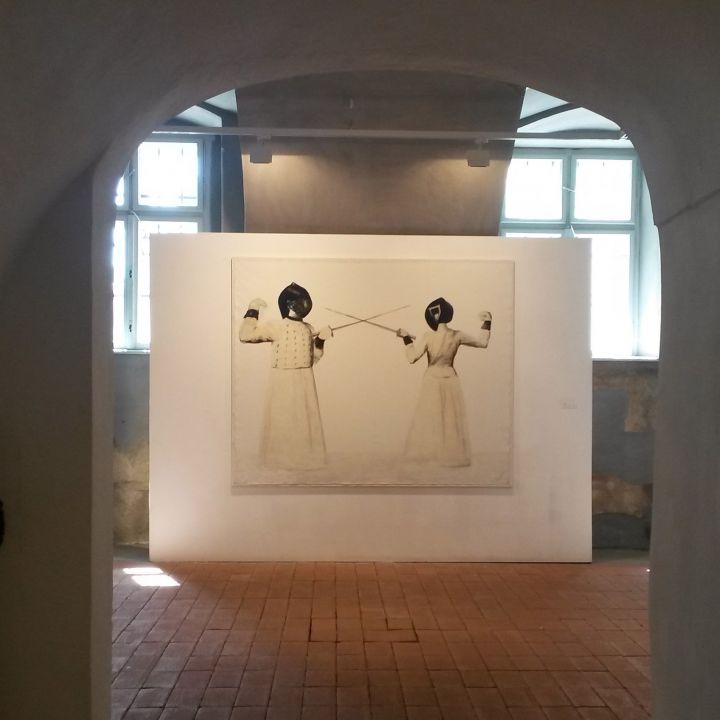

Júlia Király: The Silence of Vojnich

Well, it also follows from the person of the opening that this opening is an unconventional opening, let's say an "unconventional" opening, at most only this golden shower is conventional.

When Erzsébet asked me I immediately indicated that I could talk about monetary policy at most - she said "that's fine, just make it interesting". Indeed, there are few more exciting and stimulating topics than monetary policy.... But as Master EP says "if I had to talk about anything now, say the relationship between wolf packs and game theory with special reference to selfish genes and János Neumann - I would talk about Erzsébet Vojnich." Let us stick to monetary policy.

Monetary policy is something where the National Bank browses interest rates and makes all sorts of announcements and raises its eyebrows and waves its hands differently, and really imagines that it's going to make the world go in a different direction. Monetary policy is often referred to as an art (cf. the famous 2006 study by Olivier Blanchard - IMF Chief Economist - Monetary Policy; Science or Art?) Probably mostly because we really have no idea whether the world is really going the other way, what the effect of monetary policy is and whether it has any, and we somehow imagine that it is the same with art, that people really have no idea what the effect of a work of art, N.B. a painting, is and what makes it have an effect. (Only instead of the hermeneutics of the literati we talk about monetary transmission analysis.)

My scientist friends who used to hold Vojnich exhibition openings - sometimes contradicting each other - interpret the mechanism of Vojnich's endless staircases, empty corridors, black-white-brown pools, huge empty spaces, trying to unravel the mystery of her paintings to find the answer to the question "why do they work". Selected adjectives, words: 'seriousness, weight, power, pain, horror, desolation, elemental, sublime, meditation, incisively sharp, cool, monumental, deathly glare'. Perhaps they have been more successful than my monetary policy scientist friends. Perhaps they could try to decipher it.

All of this - browsing the interest rate of monetary policy and Vojnich's endless staircases, deserted corridors, tubs of different colours, large empty spaces, all in the days of what we call "the great moderation" - well, again, only in the happier half of the world these years marked the "end" of economic conflict, the end of a kind of Fukuyama history.

Then something happened: in 2007, a crisis began that the world had not seen since 1929-33. Or even bigger. A devastating crisis. After that nothing was the same as before. Everything changed. The world, the economy, the way economies work, monetary policy and Vojnich's pictures changed. Monetary policy was no longer fiddling with interest rates: interest rates had run out, they had vaporised into zero. They no longer had any effect, even less than before. The art of monetary policy, which has lost its ground has tried all sorts of things and is still trying - what we call unconventional (slightly unconventional) monetary policy. We know no more about its impact than we did before.

And there were little pocket dictatorships where the buffoons who fancied themselves monetary politicians thought that everything was now free. Free to use stolen money - money stolen from the taxpayer (a controversial but legitimate opinion, according to the Supreme Court) - so free to use stolen money to make foundations, to give pennies to the many, while giving billions to the few to buy banks, build palaces, etc. We have no doubt: if these PA foundations, mysteriously running on stolen money were now buying Vojnich paintings, buying up Vojnich's life's work - we would not be happy. But if the state, which rightfully uses taxpayers' money (whose task it is to maintain education, health care, culture) were to buy Vojnich paintings on its anointed organ, the "emema" - we would not be happy, but rather unhappy. It is difficult for our state to make us happy.

Well, not only have economies, monetary policies and states changed, but so have Vojnich's images. Is this related to the crisis? No? I leave the answer to my scientist friends. Gone are the endless staircases, the deserted corridors, the multicoloured pools, the gaping empty spaces - and in come the people. But one thing hasn't changed: the silence. The silence that used to dominate the corridors, the pools, the staircases - now "sounds" even more maddening. Look around you: wrestlers, dancers, fencers are dying, standing, fighting in silence. I don't know how to paint silence - only Vojnich knows. But there is no panting, no wailing, no roaring stadiums - there is silence, the silence of Vercors, the silence of terror, the silence of Iván Fischer conjured up from music in exceptional moments, the silence of the abyss.

I don't know what makes it work, I don't know how she does it. But I do know that I will sorely miss the silence of Vojnich on the walls of my room during the exhibition, which is open until the first of July.

I will open the exhibition.